Silk Road in Rare Books

Narratives on cultural heritage along Silk Road with figures and photographs from rare books.

Following in the Footsteps of Xuanzang: Aurel Stein and Dandān-UiliqRuins in the SandThe ruins of Dandān-Uiliq remain buried in the sands of the desert. The site was particularly significant to the famous British explorer M. Aurel Stein, because for it was here that Stein found one after another, relics supporting the accounts found in the work of the legendary Tang dynasty traveler Xuanzang.

Dandān-Uiliq (meaning “places of houses with ivory”) is ruins belonging to the Buddhist culture zone that once prospered around Khōtan. Famous for its jade since very ancient times, there once prospered a kingdom in the area which was known as Yutian (于闐). Even today, the bustling oasis city of Khōtan is one of the largest along the Silk Road’s Southern Route. The ruins of Dandān-Uiliq are located northeast of the present-day city in an area that was also was once inhabited by people. However, for reasons that are not entirely clear the site was abandoned at some point and in no time, it became completely buried in sands of the Taklamakan Desert. In this way the once prosperous town of a thousand years ago disappeared from people’s memories.

Dandān-Uilliq was first discovered in 1896 by Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, who is known for his crossing of the Taklamakan desert. Although Hedin understood the archaeological significance of the Dandan-Uilliq site when he discovered the remains of canals, streets lined with trees, and orchards, not being an archaeologist, he decided to leave its excavation to the specialists. He himself simply left records of the site including its whereabouts, under the title “ancient city of the Taklamakan.” Aurel Stein took particular interest in Hedin’s article and set out to see the site for himself.

In the winter of 1900, Stein set his eyes on Dandān-Uiliq for the starting point of his excavations. He began in Khōtan, where he gathered his team and prepared the necessary equipment and goods for his expedition. Upon leaving Khōtan, he first advanced northward along the river, and then changed his direction eastward, heading toward Dandān-Uiliq (Map(1)). During the day, the team dug wells seeking subterranean water sources, and at night they endured the biting cold, which at times reached as low as minus 20 degrees celsius. Thus the grueling journey continued until finally, the team reached Dandān-Uiliq(2), the site where they were to enjoy immense rewards.

After approximately a month of excavation and survey, the team confirmed the locations of as many as fourteen separate Buddhist temple ruins and monk dwellings(3). From these sites, a number of paintings on wooden boards(4), stucco figures (such as Buddha Seated on Pedastal(5), Seated Buddha(6), and Beings Born Transformationally from Lotus Flower(7)), murals, and manuscripts were found. The team also learned that the Buddhist temple ruins(8) were constructed according to a plan whereby a corridor encircles the cella (or the square center pillar layout(9)), a design created so that worshippers circled the cella with their right shoulders always facing towards the pillar as they worshipped. Paintings of Dandān-Uiliq Depicting Legends of KhōtanAmong the paintings discovered in Dandān-Uiliq are those based on the famous Khōtan legends such as the “Introduction of the Silkworm,” “the Legend of the Holy Mouse,” and “the Legend of the Dragon Lady.” Such legends appeared in Xuanzang’s famous Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (大唐西域記), and thus are quite well known.

The legend, “Introduction of the Silkworms” tells the story of the daughter of a Chinese noble who was wedded to the king of Khōtan. Although it was strictly forbidden to bring silkworms across the Chinese borders of the time, the princess hid a seed of the mulberry tree along with a silkworm eggs inside her headdress, bringing them with her into Khōtan. Stein, finding the story depicted on a colored illustration painted on a wooden board(10) interpreted the painting in light of this story so that the lady illustrated in the center wearing a headdress was seen as the princess, and that the lady-in-waiting, painted to the right of the princess was pointing at the princess’ headdress to symbolize the legend about the introduction of silkworms to the western region. Silkworm cocoons can also be seen piled in the basket shown between the princess and her maid. In the right side of the painting, another maid as well as a loom for weaving silk is depicted. Although there are different theories on the origins of silk production in Khōtan, we know that not only was silk traded in the markets of Khōtan but it was also produced in the city as well.

The second legend seen depicted in art found in Dandān-Uiliq is the Legend of the Sacred Rats” which tells the story of how the desert mice saved the city of Khōtan when it was under siege by the Xiongnu (匈奴). On one of the paintings on wooden boards(11) found at the site we find a painting of a man with the head of a rat. The man wears a crown and sits between two attendants. The figure most likely is the deified depiction of the rats of the legend.

The third legend, known as the “Legend of the Dragon Lady” is about a “Dragon Lady” who lived in a river to the east of Khōtan who demanded that the king of Khōtan provide her with a husband. The legend goes that in answer to her demand, a minister was sent to her on a white horse to become her husband. The Mural in the Cella(12) of shrine ruin D. II shows a woman bathing in a square pond with floating water lilies. In front of the pond stands a horse and it is thought that the painting most likely is associated with the legend. Although Stein had hoped to cut the mural out from the cave wall to send it to Britain for preservation, he was unable to carry this out because the stucco wall was too fragile. The Last Days of Dandān-Uiliq as Seen in Manuscripts and Coins

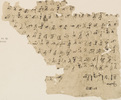

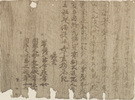

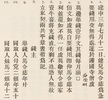

Documents written in various languages, such as Sanskrit(13) and Brāhmī(14), were discovered in Dandān-Uiliq, but the most historically significant were those documents written in Chinese which contained specific dates. For example, one document (Document Photograph(15) / Interpretation of Characters(16)) not only included the characters representing the date 781 a.d. (“Dali Year 16” 大暦十六年), but the location in which the document was produced was also listed as “Li-hsieh in “Liucheng (六城).” The record reveals that Li-hsieh was a district were Dandān-Uiliq’s temples and the living quarters were located and that Li-hsieh was part of an administrative district called Liucheng. Additional information gleaned from another Chinese document found at the site (Document Photograph(17) / Interpretation of Characters(18)) revealed that one of the ruins was that of the Huguosi (護国寺, “State Guardian”) Temple.

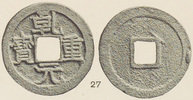

Furthermore, the condition in which the documents were found provided some hints in solving the mystery regarding the fall of the city, for all of the documents were found completely covering the floors of the buildings. One immediately wonders why the documents were left scattered on the floors in such a way, and the most likely answer is that after the documents were scattered across the floors, sand was blown into the room, weighing down the documents in sich a way that they could not be scattered in the winds. Therefore, it is believed that the dates found in these documents tell precisely when Dandān-Uiliq was abandoned. It was this which gave Stein the hint to propose that Dandān-Uiliq was abandoned around the end of 8th century. The date found on one of the coins discovered by Stein at the site matches this period with the inscription Qianyuan Zhongbao (乾元重宝)(19) -- (dated 758-9).

Why was Dandān-Uiliq abandoned? Sven Hedin, known for his “Wondering Lake” theory, suggested that the people abandoned the city because the Keriya Darya River (the north-south river on the right side of the map(1)) changed its course, moving approximately 45 kilometers east of its former location. However, Stein rejected this theory based on results he found from excavation and land measurements.

Stein, focusing on the fact that the period recorded in Chinese histories as marking the end of Tang rule over the Tarīm basin matched the last moments of Dandān-Uiliq that could be deducted from the excavated relics, posited this as the reason behind the abandonment of the city. For a desert settlement that depended on water drawn from distant rivers, the collapse of a stable government that could maintain the irrigation system would have been critical. Thus, Stein concluded that political chaos, namely the collapse of Chinese rule, was what caused the abandonment of Dandān-Uiliq. Whether Stein was correct or Hedin was correct or there was some other reason, there must have been some incident which occurred that led the people of Dandān-Uiliq to decide to abandon this settlement surrounded by the desert. Traces of Khōtan in the DesertPrior to the Dandān-Uiliq excavation, Stein had suveyed the ancient Khōtan capital of Yōtkan. However, because the irrigation system constantly brought in water and dirt, conditions at the Yōtkan site were not suitable for preserving ancient relics. Thus, Stein did not gain much from his work excavating the ruins there. It is unfortunate since Yōtkan was once a great Buddhist kingdom, which Xuanzang described as having “over a thousand temples with more than five thousand monks, who all study Mahāyāna Buddhism (“Great Vehicle” Buddhism). The king is an excellent warrior, and respects Buddhism.” Stein found far more traces of the Buddhist kingdom of Khōtan at the Dandān-Uiliq site, which at the time of the kingdom was actually only a small-scale settlement located at the distant edge of the kingdom. Because Dandān-Uiliq was a settlement created artificially by drawing river water into the desert, no one moved into the site after it was abandoned, and the it was left unaffected by water and dirt from irrigation. For this reason, the relics were preserved in good condition. In what is bleak desert, Stein discovered the abandoned ruins of temples and living quarters, ancient orchards and tree-lined avenues. He also found the traces of irrigation canals and areas filled with debris from common residences that were all reminiscent of the vivid images described by Xuanzang in his Great Tang Records on the Western Regions Stein himself would say: “How well do the things that I see and have discovered here match with what the ancient Tang monk Xuanzang described in his book about the Buddhism that once flourished in this area.” What Stein found in Dandān-Uiliq were relics could only call to mind what was described by the legendary Tang dynasty monk’s travels to ancient Khōtan as written in the Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. Stein was full of emotion as he imagined what Xuanzang must have seen when he passed through Khōtan on his way back from India. Stein was said to have constantly carried with him the Stanislas Julien translation of the Great Tang Records on the Western Regions during his excavations. Comparing the landscapes and the ruins he was looking at with those descriptions of the same places found in Xuanzang’s book, the Tang dynasty monk would come to have a special hold on Stein’s heart. And, Dandān-Uiliq, in particular stood as that special place for Stein where the Xuanzang’s travels to the Buddhist kingdoms of Central Asia, came to life. To Learn More

English Edition :

2007-10-17

English Revised Edition :

2010-03-16

Japanese Edition :

2005-04-10

Author : Makiko Onishi, Asanobu Kitamoto

Translator : Suijun Ra ; English adaptation by Leanne Ogasawara

|

Table of Content

High Resolution ImagesIndexRelated SitesNotice

|

All Rights Reserved.