Silk Road in Rare Books

Narratives on cultural heritage along Silk Road with figures and photographs from rare books.

The Transmission of Buddhist Culture: The Kizil Grottoes and the Great Translator KumārajīvaBuddhist Cave Art Preserving Profound Persian and Indian InfluencesIn the years 1906 and 1913, Albert von Le Coq, as part of the German expedition team, visited the Kizil cave site, in Xinjiang Province China. There, the German archaeologist was astounded by the great beauty of the ultramarine used in the murals decorating the walls. Reminiscent of the rich blue color of the sky, Le Coq described in his expedition diary: “…the extravagant use of a brilliant blue – the well-known ultramarine which, in the time of Benvenuto Cellini[a], was frequently employed by the Italian painters, and was bought at double its weight in gold.”[b] Derived from the mineral lapis lazuli, ultramarine comes from stones said only to have been mined in Afghanistan. The word “lapis lazuli” is a combination of the Latin word “lapis” (meaning “stone”), and the Arabic word “lazuli” (meaning “sky” or “blue”). Transported over long distances (from the area around present day Afghanistan), it was the abundant use of this pigment, deemed highly precious throughout history, which so stunned Le Coq.

In addition to the rich use of ultramarine, Le Coq was also surprised by the fact that “there was … not the slightest sign in the paintings of any East Asiatic influences.[b]”Despite its geographic proximity to China, the Buddhist art preserved in the Kizil grottoes showed a perplexing lack of Chinese elements; displaying instead more Indian and Persian (Iranian) influence. For instance, frieze murals(1) found at the time of excavation to the right and left of the great podiums showed a clear Persian (Sasanian 226-651) influence, as reflected in two Sasanian ducks with jeweled necklaces in their beaks which were drawn facing one-another within pearl-shaped medallions. Many such works created in the Indian or Persian style (displaying the artistic conventions of late antiquity) were to be found among the Buddhist art of the caves. Le Coq was deeply impressed with the art he found at Kizil, describing the murals in his diary as the “most interesting, and artistically perfect paintings.”[b] The Sasanian Empire (226-651), whose artistic conventions so influenced the murals, ruled a vast area covering the Iranian Plateau and Mesopotamia; and at its peak, extended its rule as far as Afghanistan. The cave murals found at Kizil displayed a strong influence of the art of the Sasanian Persians as well as that of India. This was particularly seen in addition to the Persian artistic conventions, in the abundant use of Afghanistan lapis lazuli. Artistic Style and Architecture of the Kizil Grottoes

The Kizil Grottoes run along the Cliffs on the northern shore of the Muzalt River(2), sixty-seven kilometers west of the city of Kucha (庫車 in Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang Province)(3). Because written records or dated inscriptions have not been found providing hints as to when the grottoes were begun, there is no standard theory on this point. A wide range of theories exist from those positing the earliest activity to have started in the third century, to those suggesting the fifth century. However, researchers generally agree that the caves were probably abandoned sometime around the beginning of the eighth century, after Tang influence reached the area.

While little also is known about when the various murals were painted, the German team proposed categorizing the art into at least two stylistic phases, and this system remains in place to this day. The murals belonging to the first phase(4) are characterized by the use of reddish pigments. In addition, the lines in the paintings are drawn carefully, and gradation shades are blended in order to give a three-dimensional appearance to the paintings. In contrast, murals belonging to the second phase(5) use abundant bluish pigments, which include the use of lapis lazuli. In addition, second phase painting shows large differentiations in pigment shades to give a three dimensional appearance to figures. As will be discussed below, many works in the Kizil Grottoes belong to phase 2.

Let us now consider the architectural layout of the grottoes. There are three main architectural styles: namely, the central pillar caves, rectangular caves, and monastic caves. However, the most unique architectural features are seen in the central pillar caves(6), which consist of three areas: the main room, the central pillar, and the corridors. The composition of the murals drawn on the walls are mostly consistent throughout.

The architecture of the central pillar caves follows an iconographic programme, functioning as the stage for the carrying out of a Buddhist pilgrimage. Entering the cave, the pilgrim would first contemplate the past lives of the Buddha as he or she passes along murals depicting scenes from these past lives shown on the walls in the main room. As part of this, the worshipper would stop to worship the main figure of Sakyamuni placed in a niche within the main central pillar. The pilgrim would next circumambulate the corridor moving in a clockwise fashion, thereby worshipping the Sakyamuni statue. Along the back walls of the corridor, the pilgrim would view scenes depicting Sakyamuni’s nirvana and there contemplate his or her own existence in a Buddha-less world. Upon exiting the corridor, the worshipper would view Maitreya (Buddha of the Future) painted on the wall above the entrance to the main room.

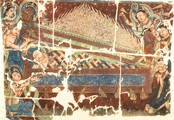

[1. The Main Room] Murals on various themes are displayed on the side walls of the main room. These include paintings on the theme of the Jâtaka Tales (本生図)(7), which are stories about the life of the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni; paintings on the theme of the Illustrated Biographies of His Life (仏伝図)(8), which depict the episodes from his life; and paintings on the theme of the Preaching Scenes (説法図, or 因縁仏伝図)(9) which depict various stories about the Sakyamuni’s preaching after Enlightenment. In a style characteristic to the Kizil grottoes, the vault ceilings of the main room are divided into diamond blocks, decorated with paintings done on these same themes (such as the Jâtaka Tales(10) and the Preaching Scenes(11)).

[2. The Central Pillars] Typically, the central pillars of the front walls contain a large nich which originally accommodated a seated figure. Surrounding the figure was a background of mountain scenery composed of built-up stucco materials. Most of the three-dimensional figures have been lost, but there are a few remains of standing figures on the front wall. However, these are mere remains and their original appearance remains a mystery. On the left, right, and the back of the central pillars are corridors with low ceilings, and there along the walls are depicted images of donors(12), monks and stūpas.

[3. The Corridors] On the back walls of the corridors behind the central pillars, we find either painted images(13) or stucco figures on the theme of Nirvana. This Kāśyapa image(14), which is particularly striking for the expressiveness of the figure as well as for its leaf patterns, is painted on this wall. The painting was originally part of the nirvana scene depicted on the back wall of the back corridor. These images represent Mahākāśyapa, the disciple who arrived late at the scene of Buddha’s nirvana, and thus failed to be there at the moment of his death. Finally, we find the Maitreya preaching in the Tuṣita Heaven depicted in the half circle above the entrance of the main room. (Line Drawing by Grünwedel(15)). The German Expedition Team

The members of the German expedition team that conducted the major survey of the Kizil Grottoes of which Le Coq was a part, left not only written records concerning the murals and cave architecture, but also compiled and left us with various other kinds of written and visual materials records on a variety of other topics, including cave floorplan measurements, site photographs, records concerning the condition of the caves, and colored sketches and line drawings of the murals. Of particular note are Albert Grünwedel’s line drawings(16), which he made by pressing a thin piece of paper directly on the paintings. These carefully done line drawings by Grünwedel as well as Ernst Waldschmidt are of great value to us today. The German Team, in addition to their onsite research, were to also cut out many murals from the Kizil site to bring back to Germany. The technique which they employed was to “cut round” the designated area “with a very sharp knife -- care being taken that the incision goes right through the surface-layer -- to the proper size for the packing-cases[b];” carefully cutting “the boundary line in curves or sharp angles to avoid going through faces or other important parts of the picture[b].” After this step was completed, they would then make a hole with “the pickaxe in the wall at the side of the painting to make space to use the fox-tail saw[b]. In cases where the surface layer of the cave walls were unstable, they would press boards covered with felt firmly onto the painting as they were being cut out.

As shown here, the paintings brought back to Germany(17) using this method had been cut into smaller parts. As a result, the walls in the Kizil grottoes are left scarred with countless blank areas where paintings have been cut out, or where the team quit their work part way through the procedure after making straight cut marks.

The cut-out paintings were transported back to Germany along with sculptures(18), painted boards(19), and manuscripts; all in all making for a magnificent collection for the German team, which far outshone anything achieved by past expeditions. The result of this excavation was compiled into reports such as the seven-volume Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien[c], contributing greatly to research on the Kizil Grottoes. Kumārajīva’s Legacy in Transmitting Mahayana Buddhist Teachings to East AsiaThe Kizil caves are located in the present districts of Kuche (庫車) and Baicheng (拝城), located in what was once the ancient kingdom of Kucha (Qiuci 亀慈). The Kingdom of Kucha was one of the great Buddhist kingdoms located along the Silk Road’s Northern Route and was known for its many temples and monks. The fourth century manuscript, Chu Sanzang Jiji (Collected Records from the Tripitaka 出三蔵記集), records that there were “over ten thousand monks in Kucha,” “countless extravagantly decorated temples,” and “palaces adorned with images of the standing Buddha, just like those seen in temples.” Furthermore, the manuscript records that there were three nunneries in Kucha in which were present the daughters of kings and nobles. The document describes the city as one of the great Buddhist centers of Central Asia. It is not clear when Buddhism arrived in Kucha, but from what one can tell from the Chinese records, it seems that already by the end of third century to the beginning of fourth century, many monks hailing from the Kucha area were in China engaged in the translation of the Buddhist scriptures. The most famous translator of them all, the monk Kumārajīva (鳩摩羅什) made his entrance into history around this time. It is not known exactly when he was born or when he died, but his major accomplishments are concentrated in the period between the first half of the fourth century and the first half of the fifth century. Kumārajīva, was the son of a Kuchean princess and an Indian father from a noble family. At a young age, he and his mother together became Buddhist adherents (his mother joining a nummery and Kumārajīva entering the priesthood). Still at a very young age, he moved to Kashmir (then part of the Gandhāran Kingdom 罽賓) to study Theravad Buddhism. In Kashmir, however, he came into contact with Mahayana teaching, and upon returning to Kucha, he dedicated himself to the Mahayana school of Buddhism. Growing in fame as a teacher, his fame reached beyond borders of Kucha borders, and it was said that his name was known throughout all of Central Asia. In Volume Two of the Kao-seng Chuan (Biography of Eminent Monks 高僧伝) it is recorded that, “the western nations all knelt at Kumārajīva’s sacred wisdom. During the annual lecture, the kings all lowered themselves before his seat, and let him step on their backs as he ascended the steps. Thus was the extent to which he was admired.” Later, due to strong requests from the Chinese who heard of his fame, he would participate in the translation of sūtras in the Chinese capital of Chang’an (長安). Chinese translations of sūtras did exist in China before Kumārajīva. However, these translations were achieved by simply utilizing the already-existing native Daoist Lao-Zhuang philosophy. Soon the Chinese began to realize the shortcomings of studying Buddhist scriptures in this manner, and therefore began a demand for translations done by foreign monks with a deeper understanding of Buddhist vocabulary and the teachings as contained in the original-language texts. Thus, Kumārajīva was the perfect candidate; for not only had he acquired Sanskrit during his studies in India, but was also thoroughly familiar with Mahayana Buddhism. Whilst instructing his students, who are said to have exceeded three thousand, Kumārajīva continued to translate important Mahayana scriptures into Chinese, including the Smaller Sukhâvatîvyûha sūtra (阿弥陀経), the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā sūtra (大品般若経), the Vimalakirti sūtra (維摩経), and the Mahāprajñāpāramitaśastra (大智度論). His translation of the Lotus sūtra in particular was thought to surpass other past translations. Due in part to Kumārajīva’s superb translations, Mahayana Buddhism was to spread throughout Eastern Asia, and soon was propagated as far east as Japan. The fact that Kumārajīva’s translations continue to be used in present day Japan shows the enormity of his achievement in the full-scale transmission of Mahayana Buddhism to the East. Not only Chinese Buddhism, but other Buddhist nations which were part of this great spread of Mahayana teachings along the Silk Road (including the great Buddhist Kingdom of Kucha), from West to East as far as Japan came to benefit from the great accomplishments of Buddhist culture.

[a] Benvenuto Cellini (1500 - 71)

A Renaissance period sculptor, painter, andgoldsmith from Florence, Italy, among his most well known works is a salt-cellar (known as Saliera) which he created for King Francis I (the work is presently in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna). Cellini’s autobiography also became quite famous as Hector Berlioz (1803 - 69) created the opera Benvenuto Cellini from the dramatic accounts recorded in the book.

[c] Out of the series, this website presents volumes 1-5.

To Learn More

English Edition :

2007-12-26

English Revised Edition :

2010-03-16

Japanese Edition :

2006-10-05

Author : Makiko Onishi, Asanobu Kitamoto

Translator : Suijun Ra ; English adaptation by Leanne Ogasawara

|

Table of Content

High Resolution ImagesIndexRelated SitesNotice

|

All Rights Reserved.