Silk Road in Rare Books

Narratives on cultural heritage along Silk Road with figures and photographs from rare books.

Ethnic Consciousness Seen Through the Letters: Khara-Khoto and Western Xia CharactersDiscovery of Khara-Khoto Unravels the Mystery of an Ancient Dynasty

Aproximately 80 kilometers north of Beijing, near the most-visited part of the Great Wall, is the legendary Juyong Pass (居庸關), Standing at the pass is the Crossing Street Tower(1). The Tower is also called “Cloud Platform,”as there once stood three white towers on top of it. The three towers were destroyed in the transitional period between the Yuan Dynasty and the Ming Dynasty and today only the platform remains. The origin and history of the tower are written on the walls of both sides of the arched door of the platoform in six different scripts. Five of the six scripts were long ago identified as Sanskrit, Tibetan, Phags-pa, Uighur, and Chinese, but the last script remained a mystery. This mystery was finally solved in the 19th century when the French Orientalist Gabriel Devéria figured out that it was the Western Xia (Xi Xia, Hsi Hsia, 西夏) language. The Juyong Pass had been built in 1345—a date not all that long ago considering the long history of China—and so one wonders how it came to pass that this one language had been so completely forgotten? The Western Xia language was created by the Western Xia Dynasty (1032-1227), which ruled over the northwestern part of China (today’s Ningxia, Gansu, and Inner Mongolia Provinces). The empire was established by the Tanguts and thrived, like other nomadic empires, such as the Khitan and Jurchen Empires (Liao and Jin Dynasties), around the time of the Song Dynasty. It was later overthrown by the Mongols under Genghis Khan. During the period of the Yuan Dynasty, the histories of the Liao, the Jin and the Song were compiled as Three Historiographies of the Yuan Dynasty. However, the history of Western Xia Dynasty was not compiled, nor was the Western Xia language all but rarely recorded in documents. But the scriptcarved on the wall of central door of the platform is clear evidence that some people at least were still able to read and write the Western Xia language even 100 years after the dynasty had collapsed. As time went by, however, the number of people who understood the language declined, and finally no one was left who could recognize it any more. A major archeological discovery turned things around. In the early 20th century, the Russian explorer Pyotr Kuz'mich Kozlov found the ruins of Khara-Khoto, which literally means “black city” in Mongolian.

Kozlov had come to Mongolia from Russia in 1907, intending to explore Mongolia and Sichuan. There local people informed him of a terrifying ruined city which was believed to be cursed and haunted. Intrigued by the story, Kozlov visited the ruins of Khara-Khoto located to the east of the lower reaches of the Edsin-Gol River (Photo(2), Map(3)). He discovered in the ruins Buddhist statues, Buddhist paintings, coins, and 30-odd books written in a mysterious language. Not knowing when and which people compiled the manuscripts, Kozlov sent his findings to the Russian Academy of Sciences. Later they were revealed to be important remains of the Western Xia Dynasty. On his way home from another site, he revisited the site in 1909, and collected a great number of Western Xia relics, including more than 2,000 documents and about 300 Buddhist paintings. Kozlov’s findings dramatically helped develop the study of the Xi Xia Dynasty as the documents found at Kara-Khoto revealed many unknowns facts about Western Xia society and its culture. Therefore, it was the excavations at Khara-Khoto--, Kozlov's greatest achievement-- which brought about the decisive turning point in Western Xia studies. The Ruins and Relics of Khara-Khoto

During the period of the Western Xia Dynasty, Khara-Khoto was known as “Heishuicheng,” which literally means, “Black Water Town.” The remaining town walls are 421 meters from north to west and 374 meters from north to south (Sketch Plan of Ruined Town of Khara-Khoto(4). Gates, about 5.5 meters wide, lead through the western and eastern wall faces, each protected by a rectangular outwork. The town walls were defended by big circular bastions at the four corners and by rectangular bastions (馬面, literally “horse-face”) along the side at regular intervals; four on the western and eastern faces, six on the north, and five on the south.

Although it was Kozlov who made the most contributions to uncovering and studying the ruins, the British archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein also visited Khara-Khoto during his third Central Asian expedition in 1917, six years after Kozlov. Stein surveyed the area for eight days and compiled his research results in chapter 13 of his first volume of Innermost Asia, which included his sketch plan of site of Khara-Khoto(5) and pictures of the excavated antiquities.

Stein made some remarkable discoveries at Khara-Khoto, though he could only see those items left behind by Kozlov. Most of the documents Stein gathered were fragments. For example, among the Chinese manuscripts, he found nine documents dated between 1290 and 1366. These records proved that Khara-Khoto had long been inhabited until the period of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) even after the fall of Western Xia Dynasty. This fact was verified again by the survey proceeded by Inner Mongolia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (内蒙古文物考古研究所) and Cultural Relics Station of Alashan (阿拉善盟文物工作站) in 1983 and 1984. Through these surveys, it was found that the small square town of 238 meters long had been built in Western Xia period and had been expanded to the west and south, as we see today, during the Yuan period.

The western and eastern parts of the town were very different from each other. Judging from the roof tiles scattered in the western half of the area, many temples with tiled roofs and government offices must have stood in that part of the town. In the eastern part, however, no roof tiles were found. Roofs were made of stamped clay, covering the timber ceilings. Buildings inside the town were built of bricks, but the remains of their structures were mostly gone, with decomposed clay and small debris mostly found spread over the town.

Countless fragments of pottery and porcelain were found scattered on the ground Fragments of Glazed Pottery, Porcelain, etc.(7). This showed the wide spread of the custom of tea drinking after the Song period, as well as the expanse of the market of Chinese ceramics to the north and west via Khara-Khoto. Various kinds of ceramics were found in Khara-Khoto; Cizhou Ware (Cizhou district in Hebei Province) decorated with scratch incised patterns, white Ding ware (Quyang district in Hebei Province), Yaozhou Ware (Tongchuan district in Shanxi Province), Jun Ware (Yu district in Henan Province), Longquan Ware (Longquan city in Zhejiang Province), Qinghua Ware decorated with cobalt on a white porcelain body (Jindezhen in Jiangxi Province) in Yuan Dynasty, and so forth.

A group of Tibetan-style stūpas stood outside the town’s fortress walls (Photo(8), Plans and Sections of Stūpas and Shrines(9)). Stucco images and paintings discovered there show no real Western Xia-influence; instead being strongly influenced by Tibetan Lamaism (Blockprints on Paper(10)) or by the art of the Song Dynasty Standing Figures of Bodhisattvas(11), Standing Guardians of the Temple(12)). Kozlov discovered a number of documents and paintings from inside the stupas, and Stein also collected many fragments of stucco reliefs and Buddhist figures (Heads of Buddha(13), Portions of Stucco Armour(14)). The Western Xia Seen through their ScriptAmong the various clues found in Kara-Khoto, it was the manuscripts written using the Western Xia script which were the most decisive in solving the major mysteries of the dynasty. The struggle to decipher those manuscripts also promoted the study of the Western Xia language and its characters.

The Western Xia language(15) was invented by Yeli Renrong (野利仁栄) and other scholars. The founder of the dynasty, Li Yuanhao (李元昊), issued a decree ordering the invention of an original script for the language as one of the founding projects of his rule. The scholars involved in this project sought to develop a variation of the Chinese characters, in an effort to set their dynasty apart from the Chinese language and its culture ( though it is thought that some Chinese scholars participated in the project). In 1036, the newly-created Western Xia language became the government-designated language. The study of the Western Xia language was launched in France, and it advanced remarkably after Kozlov’s discovery of Khara-Khoto. Kozlov’s findings included dictionaries which became indispensible for the study. These dictionaries included the Western Xia-Chinese bilingual glossary, Bo Han He Shi Zhang Zhong Zhu (蕃漢合時掌中珠) and the book on Western Xia pronunciation written in Western Xia characters, Tong Yin (同音). Because of the intense desire to translate classical texts into the new language, many translated versions of Chinese or Tibetan Buddhist scriptures and Chinese classics, such as the Analects of Confucius, the Classic of Filial Piety, and Sun Tzu’s Art of War, were found at the site as well. These all proved helpful in understanding the language. Russian scholars Ivanov and Nevsky as well as Chinese scholar Luo Fucheng contributed greatly to the research. Also, the Japanese scholar, Tatsuo Nishida played a vital role in advancing research in the language.

According to Nishida, the Western Xia language consists of more than 6,100 characters, most of which are ideograms or, properly speaking, logograms. There are almost no pictographs like the Chinese “山” (mountain) or “川” (river). On the contrary, the Western Xia conveyed concepts through semantic elements, composing individual characters by combining necessary elements. Experts have confirmed that there were 350 elements and 44 methods of combination.

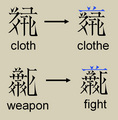

While some of the elements for forming the Western Xia characters are similar to Chinese radicals (or classifiers), Western Xia characters can represent different meanings with the same elements by positioning the elements upside down or switching the right side with the left (Elements of “Water” and “Fish”, “Branch” and “Leaf”(16))[a]. Elements with similar meanings tend to have similar shapes (Radicals indicating “person”, “animal”, and “insect”(17))[a]. There is also a radical that represents “negative” and cannot be seen in Chinese (“gather” and “disperse”, “forget” and “remember”(18))[a]. A crown radical changes a noun into a verb (“cloth” and “clothe”, “weapon” and “fight”(19))[a].

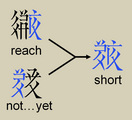

As Western Xia characters were thus formed by combining several semantic elements, its system is rational and well-organized. It is possible to interpret meanings of each character by association. One of the most fascinating points in studying the language is that we can see something of the Western Xia people’s way of thinking through deciphering their characters. For instance, the Chinese characters “鈴” (a little bell) and “鐘” (a bell) have a radical which means “metal” and both belong to the category of metal. In contrast, the equivalent Western Xia characters utilize a radical which means “sound” and belong to the category of items of sound production. The Western Xia character which represents “short”(20)[a] has a radical meaning “not yet” and has the other element meaning “reach”, while the Chinese equivalent “短” consists of the parts which mean “an arrow” (矢) and “small one-legged tray” (豆).

Another interesting instance is the character which represents “China / Chinese”(21)[a]. The character is composed of the elements meaning “small” and “insect.” This derogatory word symbolizes Western Xia’s sense of rivalry and pride against China, claiming their superiority over it. Ethnic Consciousness Seen through Language InventionAt the time when the Western Xia Dynasty flourished, China proper was ruled by the Song Dynasty. Song military power was very weak weak and its territory was so small that foreign dynasties thrived around it. The Liao Dynasty (916-1125) and the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), which emerged at almost the same period with Western Xia Dynasty, established stable foundations. The Liao Dynasty, in particular, grew strong enough to have equal diplomatic relations with the Song and was known for its cultural achievements as well as its military achievements. China had lost its absolute power of the past. Under these circumstances, the foreign dynasties around China became more conscious of their on unique cultural heritage and ethnicity. The Tangut, who established the Western Xia Dynasty, were originally a small tribe living around the western part of Sichuan-, wedged between the Tibetan tribes the Tubo and the Tuyuhun. At the end of the Tang period, oppressed by the power of the Tubo, the Tangut moved northeastwardly into the Ordos region, inside the southern area of an immensely great bend of the Yellow River. Until the period of the Five Dynasties and Early Song, the tribe extended its power by supporting the Chinese dynasty. The chieftain was even bestowed the imperial surname of Li by the Tang Dynasty. As they grew stronger, however, in the time of the emperor Li Jixuan (李継遷), the Tangut rebelled against the Song Dynasty, and his Li Jixuan’s grandchild Li Yuanhao declared their independence in 1032. He established his capital at Xingqing-fu (i.e., today’s Yinchuan) and enjoyed great prosperity by ruling over the important trade route along the Hexi Corridor. It was Li Yuanhao who also gave the order to create a new writing system. A young and patriotic leader, Li -along with his people- must have felt great pride in their culture having broken away from vassalage to China. As ethnic consciousness increased among such outlying peoples, language invention was thought to be a symbol of their own cultural identity and therefore other outlying tribes and peoples began to engage in the practice of language invention. Not only the Western Xia, but also the Liao Dynasty created the Khitan characters and the Jin Dynasty created the Jurchen characters. The Influence of the Turkish Uighurs should also not be ignored. They built a powerful empire to the north of the Tang Dynasty, which was then destroyed by the invasion of Kyrgyz at the end of the Tang period. At that time, the Uighurs dispersed to the east and the west. The Uighurs who escaped to the east drifted into the territory of the Liao Dynasty. Contact with Uighurs who used their own characters, which were completely different from Chinese, is considered to have triggered the awakening of ethnic consciousness among the Khitan people in Liao. The Khitan language had two kinds of characters: the large script made by the founder Yalu Abaoji and the small one created by his son Dieci. The small script contains many phonograms based on the Uighur characters, though their forms bear a close resemblance to those of the Chinese characters. The Uighurs who escaped to the west invaded countries in the South-of-Tianshan Circuit where they expelled the Iranian culture that had long thrived there. This brought about the greatest change in the history in the Tarim Basin, as it was at this time that the main inhabitants of the area came to be the Uighurs, who had replaced the previous Iranians people. The came to be called Turkestan, which means “land of the Turks,” later on. Thus the migration of Uighurs caused drastic changes in the Silk Road regions. The uniqueness of Uighur culture, such as the Uighur language, triggered long-lasting increases in ethnic consciousness of peoples in Khitan, Western Xia, Mongolian Yuan, and Manchurian Qing.

[a] Plates of Western Xia characters were made using Mojikyo fonts. The code numbers of the characters mentioned above are as follows. Each character can be searched by entering the code number below into the last four digits (@57xxxx) of Mojikyo number.

To Learn More

English Edition :

2008-02-05

English Revised Edition :

2010-04-14

Japanese Edition :

2005-10-10

Author : Makiko Onishi, Asanobu Kitamoto

Translator : Yasuhiro Itami ; English adaptation by Leanne Ogasawara

|

Table of Content

High Resolution ImagesIndexRelated SitesNotice

|

All Rights Reserved.