Silk Road in Rare Books

Narratives on cultural heritage along Silk Road with figures and photographs from rare books.

Central Asian Buddhism: Turfan and the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha CavesThe Lost Murals of Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

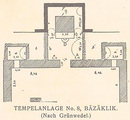

Approximately a hundred years ago, when the German expedition (09) to Central Asia led by Albert von Le Coq reached the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves near Turfan, they found the site almost completely buried in sand and inhabited by local nomads (Distant View of the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves(1), Sketch of the Bezeklik Cave drawn by the German Expedition Team(2), Floor Plan of the Bezeklik Cave drawn by Albert Grünwedel(3)). Although the Uighur word "Bezeklik" means "a place with paintings" or "a beautifully decorated place," the caves were in such a terrible state of disrepair that no one could ever have imagined the reason behind the name. However, as the German archeologists began clearing the deep layers of sand that had accumulated inside the caves, they were stunned when murals painted in the most extraordinarily beautiful colors appeared before their eyes (Seated Buddhas(4), Dragon Pond Scene(5)).

Visitors to the caves today, however, will no longer find exquisite murals adorning the cave walls. What happened, they will wonder, to the murals discovered here a hundred years ago beneath desert sands? The reason behind their disappearance from the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves has to do with the survey methods used by the various international expedition teams that traveled to the area from nations, such as Germany, Japan and Britain. Removing murals, manuscripts, and Buddhist sculpture from the caves, the foreign expeditions took the art and artifacts back with them to their respective homelands as the fruits of their labor in the Central Asian deserts. In particular, the German team removed a great number of murals-- as many as could be cut out and carried back home. (See, for example: Image of Vaiśravaṇa(6); Precious Flower Pattern(7); Scenes of Reincarnation into the Six Destinies(8) etc.). The sad fate of the murals would only get worse as many of these paintings, stored in a museum in Berlin were lost forever in air raids during the Second World War.

Today, therefore, all we have left of the murals taken by the German expedition are the photographs and sketches that the team left behind. Contained in the Toyo Bunko Rare Book Digital Archive are some of the expedition team’s survey reports. The books provide a glimpse into the great beauty of the murals that once decorated the cave walls of Bezeklik. Below we will introduce some of the murals that have been digitally-reconstructed based on books in the Toyo Bunko collection. The Uighurs Depicted in the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

The Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves site is located in Turfan(9), a key junction on the historic Silk Road’s Northern Route. During the late eighth century, the Uighurs, who were devout Buddhists at the time, occupied the area. The Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves were the largest of the various Buddhist monuments that the Uighurs had a hand in constructing around Turfan. We find in the cave murals and in other artwork, such as Buddhist banners excavated in neighboring ruins, Uighur royalty and nobles depicted as religious donors. These artworks give us an idea of how the Uighurs looked at the time.

The piece, "Male Donors(10)" (9-12th century), for example, is painted on a bright vermillion background, with colorfully dressed male donors lined up in two rows. Each donor holds a flower in both hands with Uighur inscription alongside each. One can see that the style of headdress differs between the group of eight donors on the upper row, the four donors on the right half of the lower row, and the four donors on the left half of the lower row. "Female Donors(11)" (9-12th century) depict Uighur women wearing their hair in a distinctive hairstyle which sticks out horizontally at the sides. The women adorn their hair with accessories shaped in the form of auspicious clouds, and are wearing crowns in the shape of the sacred jewel. They stand with their hands clasped together in front of their midsections.

In the artwork depicting Uighur donors, such as those shown here, donors are usually portrayed in multiple rows. However there are some that feature a particular donor, such as the piece,"A Donor(12) (9th century)." In the piece, we see a man, probably royalty or a noble, shown standing holding a flower in his hand. Another example is "A Banner with a Portrait of a Donor(13)" (Outline of the Painting(14)) which was discovered at the nearby ancient city of Gaochang (高昌, also known as Chotscho or Kharakhoja). Exceeding 140cm in length, the large banner is unique among its kind in that it features a large figure of a donor in the main part of the banner. The nobleman, who has snow-white hair and a thick moustache and beard, is holding a flower in his hands. A small child is painted on both his left and right sides. The Praņidhi Scenes of Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

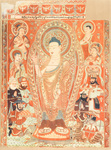

The mural that best represents the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves is the large-sized mural, which was given the name the "Praņidhi Scene(15) by the German expedition team. The mural was given this name because it was judged to be a painting depicting Sakyamuni’s "promise" or "praņidhi" from his past life.

What exactly is "Sakyamuni’s promise from his past life"? Buddhism inherited the traditional Indian world-view that humans are reincarnated countless times, and that every phenomenon happens due to karma. This means that every event has its own cause or reason for its occurrence. Stories were thereby created to explain the Karmic reasons behind Sakyamuni’s gaining enlightenment and becoming a Buddha. The stories tell of how Sakyamuni in his past lives worshipped the Buddhas of the Past (過去仏), and how in return, the Buddhas bestowed upon him the prediction or prophesy (vyākaraņa 授記) that he (Sakyamuni) should gain Buddhahood in the future. The most well known among these prophesy stories perhaps is the story concerning Dīpaṃkara Buddha, or the " Dīpaṃkara Jâtaka (Mural in Bezeklik Cave 9(16)[a], Relief Excavated from Ghandara(17))." According to the story, once, a young brahmin named Sumedha (also known as Megha) heard that the Dīpaṃkara Buddha was coming to the city, and decided to make an offering of lotus flowers to the Buddha. However, the king who also was hoping to make offerings to the Buddha had bought up all the lotus flowers in the kingdom, leaving hardly any for others to purchase. However, Sumedha persistently continued his search, and he came upon a girl with a vase of lotus flowers. Sumedha begged the girl, who finally agreed to spare him some flowers. When Sumedha offered the lotus flowers to Dīpaṃkara Buddha, a miracle occurred. The flowers rose into the air and stayed above Buddha’s head. Sumedha also noticed that a pool of mud lay in the Dīpaṃkara Buddha’s way, and so Sumedha lay on the ground and spread his hair out on the pool to prevent the Buddha’s feet from getting soiled. Noting Sumedha’s piety, the Dīpaṃkara Buddha prophesized that Smedha would be reborn someday as Sakyamuni and that he would thereby gain enlightenment. The "Praņidhi Scene" of Bezeklik is based on this type of prophesy (vyākaraṇa) story. The theme can be seen in many of the caves, painted on the walls on both sides of a circular corridor, in a succession of multiple panels. Although there are many variations in its iconography (a 3D model of cave 9 [a]), the basic constitution of the panels remains the same. The panels all feature a large standing Buddha figure in the center, most likely depicting one of the past Buddhas such as Dīpaṃkara Buddha, with worshippers (dressed as royalty or Brahmins) showing their devotion around the Buddha. The figures of worshippers most likely represent Sakyamuni in his past lives. The grounds for such interpretation are that within the inscription accompanying the "Praņidhi Scene," one can find words matching the content of the sutra Nagarānalambikāvadāna. This sutra belongs to the school of Hīnayāna Buddhism called the "Sarvâstivāda School" which was quite popular in Turfan at the time, and a part of this sutra tells such vyākaraṇa stories. Thus, it is fairly clear that the Bezeklik "Praņidhi Scene" was created under the influence of the Sarvâstivāda School, in line with the wish of believers to follow in the footsteps of Sakyamuni to gain Buddhahood. The German Expedition Team Surveys and the Post-Expedition Fate of the MuralsThe Buddhist caves were completely abandoned around the mid-fifteenth century to mid-sixteenth century when local population converted to Islam. By the time that the German expedition team reached Bezeklik, the caves were buried beneath thick layers of sand and sediment. However, being buried in the sands of the desert actually had a positive effect on the murals, effectively protecting them from the raging wind and other climatic conditions of the area. Indeed, the paintings were discovered in nearly perfect condition and Le Coq left this account of their excavation :

The narrow corridors, which in these temples often encircle the cella, existed here, too, but were filled from the floor to the top of the walls with fairly compact mountain sand. With some difficulty I got on to these heaps of sand in the left corridor, and as I clambered up the sand slipped down under the weight of my body, so that by constantly lifting my feet high and stamping to get foothold I dislodged many hundredweights of the heap lying there. Suddenly, as if by magic, I saw on the walls bared in this way, to my right and left, splendid paintings in colours as fresh as if the artist had only just finished them. (Original Text(18)) The "Praņidhi Scene" was the highlight among the collection of works that the German expedition team brought back from the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves. Upon their safe transport to Berlin, the murals were exhibited in the Berlin Ethnological Museum (Display Layout of the Berlin Ethnological Museum Prior to Air Raids(19)). However, due to the fact that the paintings were permanently fixed to the walls of the building, the pieces were affected directly by the air raids in 1944 during the Second World War, and were almost completely destroyed.

The German team did, however, create thorough expedition reports and catalogues (Floor-plan of Cave 8(20)[b]). In particular, publications such as Le Coq’s Chotsho (Berlin, 1913) and Grünwedel’s Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan (Berlin, 1912) contain ample supply of plates including the "Praņidhi Scene," along with very thorough expedition and scholarly reports. These are now almost the only resource we have of lost works such as the cave 9[a] mural, which was the highlight of the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves (Floor Plan of Cave 9(21), Layout of the Murals in Cave 9(22)).

[a] Number according to the German expedition team. Present cave 20.

[b] Number according to the German expedition team. Present caves 18 (center) and 19 (left).

To Learn More

English Edition :

2007-09-18

English Revised Edition :

2010-03-16

Japanese Edition :

2007-07-13

Author : Sonoko Sato, Makiko Onishi, Asanobu Kitamoto

Translator : Suijun Ra ; English adaptation by Leanne Ogasawara

|

Table of Content

High Resolution ImagesIndexRelated SitesNotice

|

All Rights Reserved.